In this project I had complete freedom to address any issue I wanted to, and I chose to work with humanitarian organisations to improve the quality of life for internally displaced people in refugee camps. I did extensive research to establish that the largest issue in camps in Northern Syria is food access and nutrition, and set out to develop a kit of tools, components and instructions to enable the creation of water-efficient farm systems made from available materials which have been upcycled.

Early Research

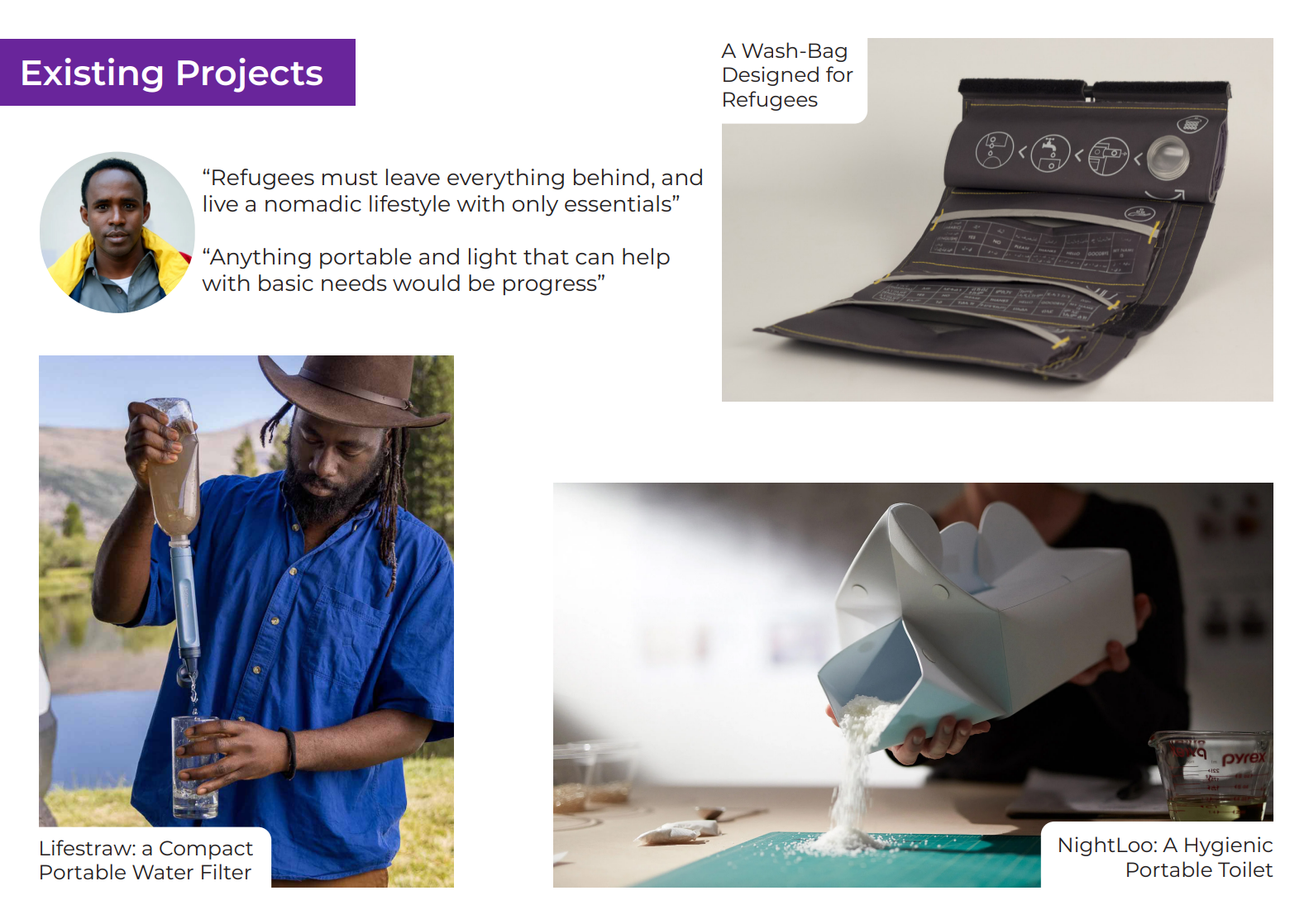

I began with extensive secondary research into humanitarian issues, the politics and logistics of immigration. I also looked into what existing projects already aim to improve conditions for refugees. I then reached out to the New Communities Project (NCP) to speak with some refugees directly. I conducted a survey with some of their members where I asked about their experiences and gathered information about the challenges that they have faced.

I contacted Julian Tung from CARE International (a prevalent NGO) to discuss the challenges of improving conditions in camps, as well as Ana Cristina Tavares, a psychologist who had worked with refugees on rehabilitation and trauma management. I also spoke to Warsame Ali Garare, a former refugee and current human rights Lawyer about his experiences and the ways the things that matter the most as a refugee.

I also joined the 'Sanctuary Runners', an organisation that hosts weekly 5K runs for Asylum Seekers here in Ireland, and for those who want to show solidarity. I met some very interesting people there including Mohammed and his family who came from Yemen, and told me of the difficult experiences they had faced in turkey and greece, and how the system in Ireland was unable to support them, leaving mohammed and his brothers to sleep in a cold tent during the Irish winter.

Finding a Need

I managed to get in contact with Khalil Al Taha of CARE International, the civil planner for multiple Syrian Refugee camps: including one in North-West Syria called Zoghara. This camp of 11,ooo people is very established, and has good basic infrastructure such as sanitation, internet, and effective prefabricated shelters. However, in Zoghara, consumables such as food are in very short supply, and the budget for aid has been substantially reduced leaving many in the camp reliant on less than 60 euros a month of aid to survive on. Inhabitants could also often not work as there were few opportunities in such a camp, despite CARE international's best efforts. Khalil was enthusiastic about a project that may be able to supplement food supplies and strengthen the camp's economy, so I set to work developing concepts.

Concept Development

Focussing on the need for food, I developed concepts for different types of agricultural systems would be water-efficient and possible to construct using basic materials, ideally even ones that were already available in the camp. I analysed my concepts based on how water efficient they could be, how difficult it would be to source materials for them, the amount of variety of crops they could support, as well as how difficult they would be to assemble.

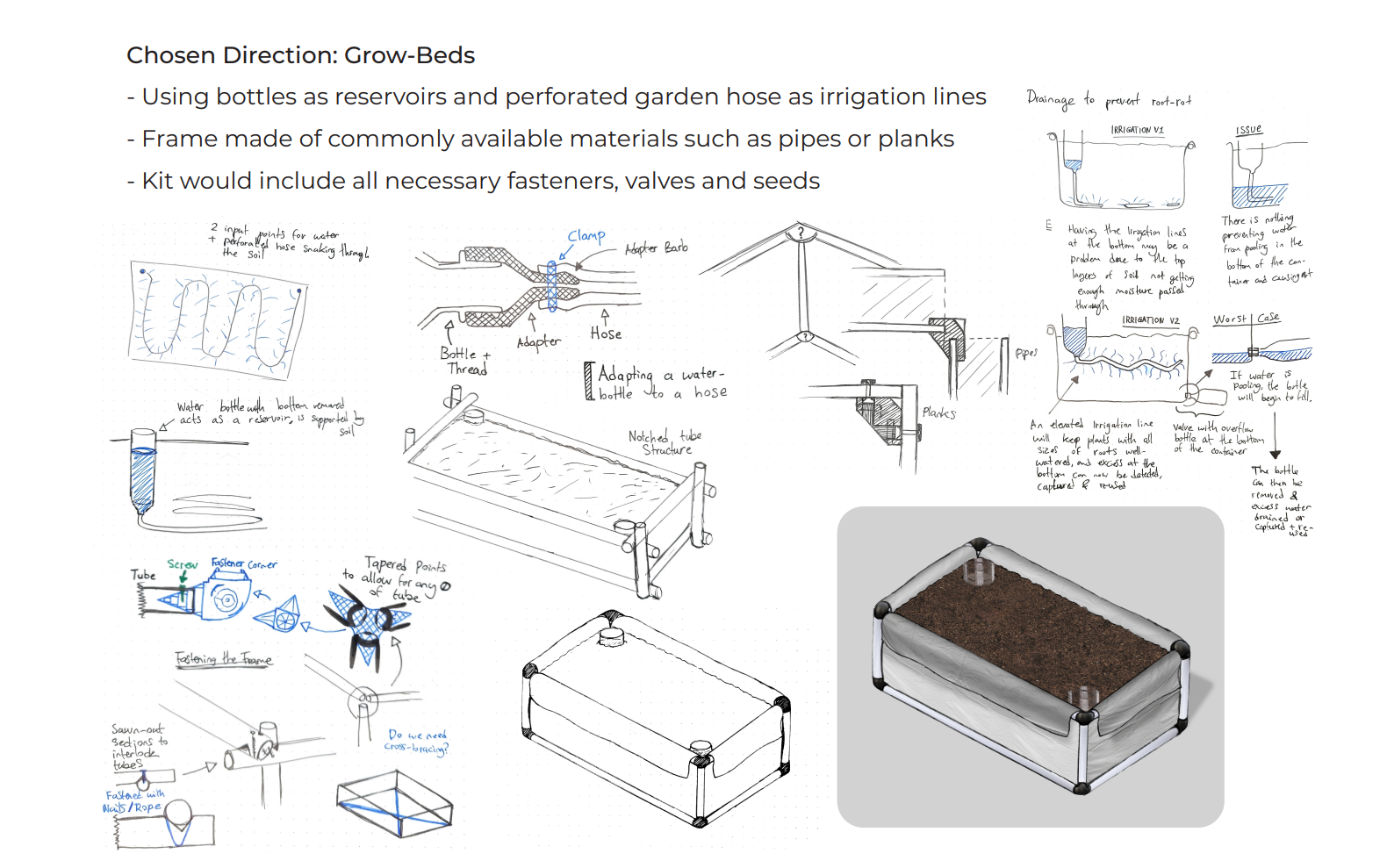

I opted for the 'Grow-Bed' concept, and began developing the concept through sketching, theorising about how an irrigation system would work, and did research into drainage systems, water collection and re-circulation. I also considered how the system could be assembled, and opted to start developing some universal corner pieces which would allow for a variety of pipes/planks/poles to be used as the structure of the container. I opted to use conventional water bottles as reservoirs for the system as these are widely available and generally standardised so I could use the same thread for all of the adapters.

Early Testing

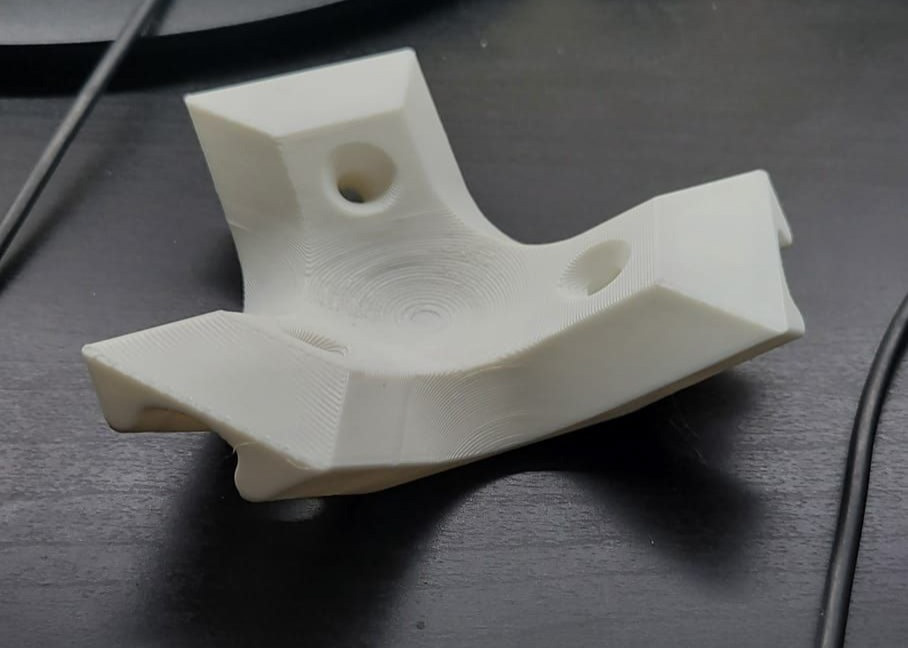

I modelled and 3D-printed some early drafts of the necessary adapters and ports, and used a plastic container as a scaled-down draft of the system to ensure that the irrigation and drainage system would work. I tested different sizes and tools for the perforations in a garden hose to act as an the irrigation system, as well as different filter systems for the drainage port. I iterated on the designs of the adapters and ports based on lessons learned during this testing.

Scaled-Down Testing

Before creating full-sized prototyped I wanted to make sure that the system would work, so I germinated a wide variety of different seeds and planted them in these plastic containers alongside the irrigation and drainage systems. I began with 2, but throughout the projects expanded to 5 of these containers, each packed with plants. This testing helped me to decide which seeks would be provided with the kit, depending on their speed of growth, how much space they would need, h0w water-efficent they were, and how quickly they yielded edible vegetables.

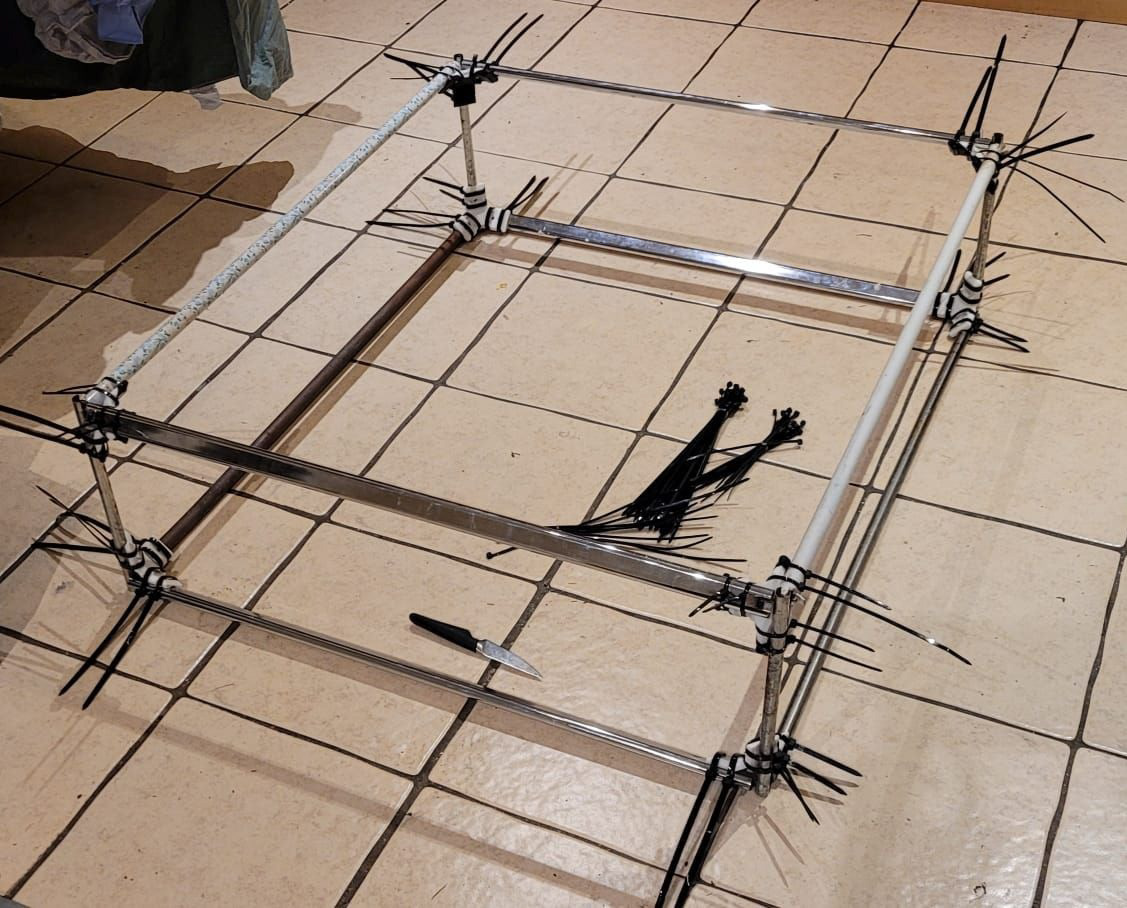

First Full-Scale Prototype

The first scale prototype included a drainage system as well as a covered greenhouse in order to create a closed-loop system to capture and conserve water. The frame was made from purchased PVC Pipes, but all other components were sourced from my environment: The lining of the container is a recycled old tent, the crossed beams which support the greenhouse are recycled tent poles, and the clear plastic of the greenhouse is recycled packaging. I also built this structure using a combination of screwed corners and zip-tied corners to ensure that both were stable enough to function for a structure this large.

Iterative Improvements

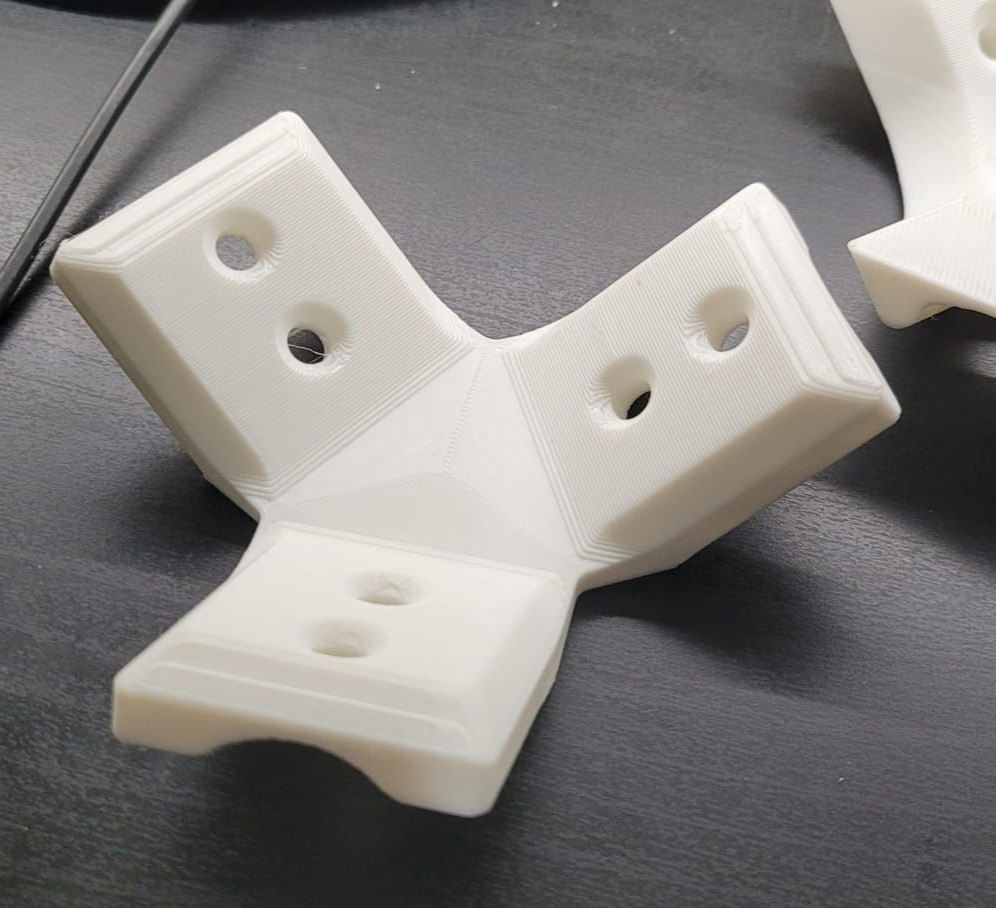

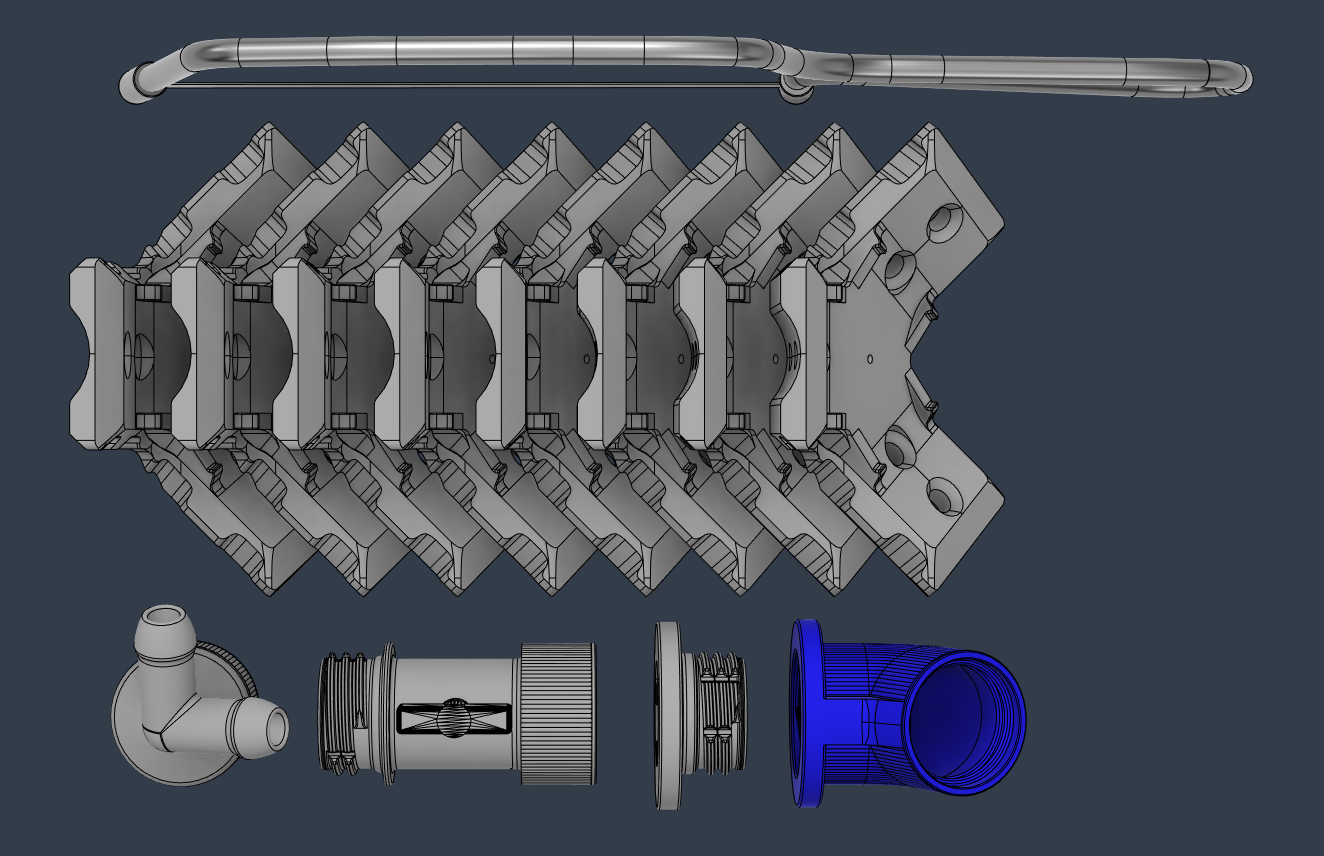

I designed these corner pieces to secure the frame of the full-sized system together in a flexible way, and as I tested this with different prototypes, I made constant improvements, aided by 3D-printing to rapidly implement these changes as the models progressed.

These parts began as simple joints which would allow pipes to be screwed in place, but as the availability of steel pipes from tent frames in Zoghara became more clear, I began to design in slots for zip-ties to secure pipes in place instead of screws, as I wanted these parts to be as toolless as possible, otherwise my kit would have to become a lot more complex and include much more expensive parts, making it less scalable.

I also stress tested each of these iterations with a lot of weight, and made improvements to the structure when versions would fail these tests and crack.

Second Full-Scale Prototype

This second proper prototype sought to improve upon the process used during the first one, as some aspects had been unnecessarily messy. For this prototype I used waste metal pipe for the frame to test how feasible the exclusively zip-tied frame would be. The lining is a tarpaulin, and the process of lining the container was refined considerably since the last version. I did not put a greenhouse on this one as I was already satisfied with that aspect of the design, and this model is a different size due to the frame being made from excess metal scrap, so the top is not interchangeable.

Challenging assumptions

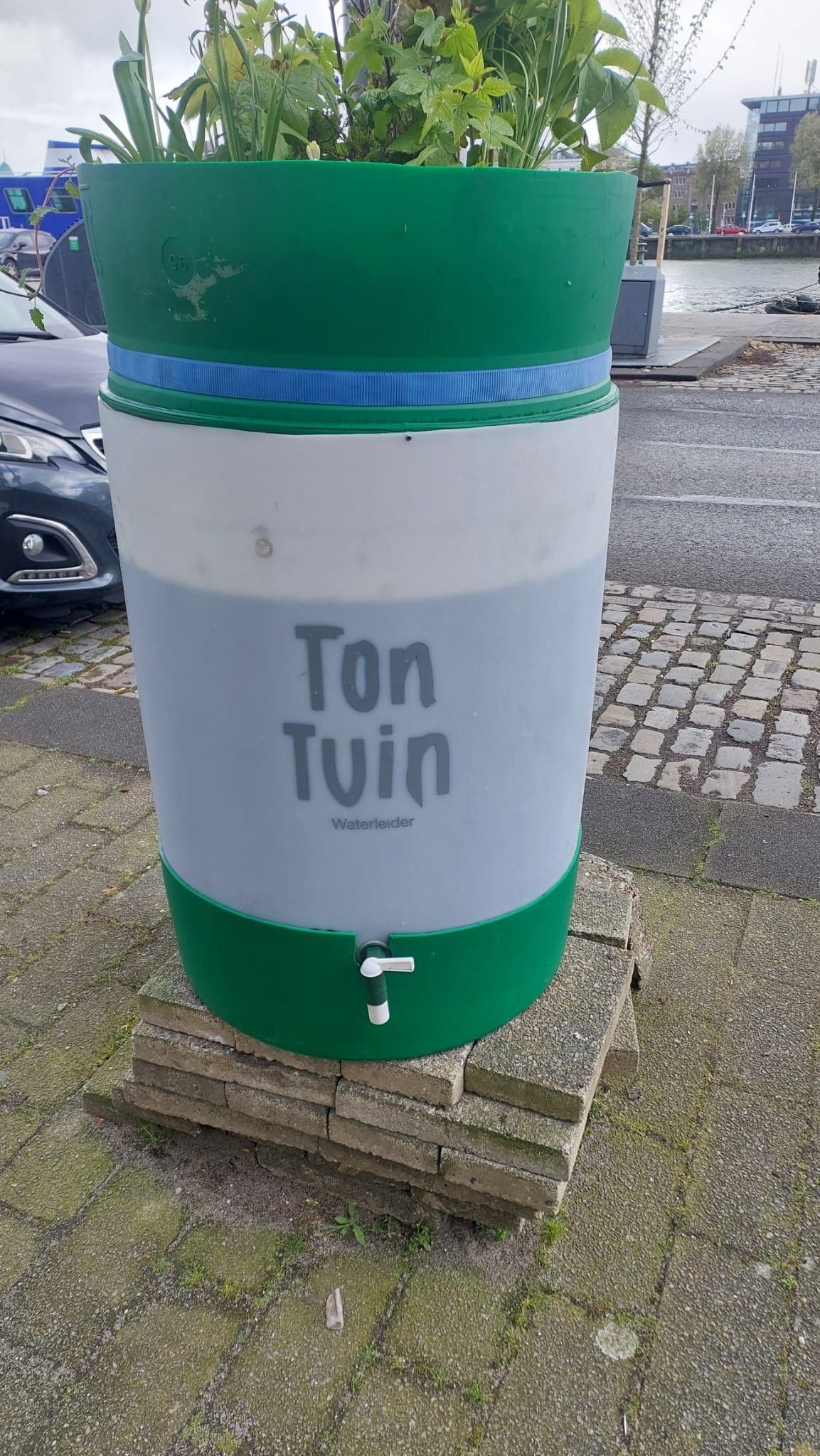

Through continued collaboration with Khalil in Syria, I ensured that the materials required for the kit were in fact available and accessible for refugees. I did this by requesting that he send me pictures of examples of these materials in the camps and surroundings, and also did my own research by contacting hardware shops and asking which of the materials they stocked, as well as ensuring that the price would be reasonable and worthwhile for IDPs in Zoghara and other camps.

Continued Research

To verify the viability of my concept and hear feedback, I reached out to Daniel Amoak and Bashir Al Awar of ICARDA (The International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas. Daniel is an expert in seed technology and agricultural projects and Bashir is a farming systems engineer.

Daniel gave me great feedback and support on the circumstances of the project, establishing that such a project would be desirable in subsaharan Africa as well as the middle easy, as accessible, water-efficient farming is very desirable and not well catered to. He stressed the importance of empowering women through this system, enabling them to earn with their farms as well as giving them and their families more independence through their more flexible access to food. He emphasised the importance of not supplying more seeds than necessary, as seeds should be local in the long-term to ensure efficiency and sustainability.

Bashir gave me feedback on the system itself, and we made some adjustments to the drainage system initially. Bashir introduced me to some interesting comparable projects and alternative technologies, although we agreed to keep the system as simple as possible for the sake of accessibility. Bashir also offered to construct such a system at his office in Beirut, Lebanon as a trial, and to ensure that the system would work in the desired climate. This was a great opportunity as Bashir could also suggest further improvements if he had the system available to test himself. I sent off an early draft of the kit as soon as possible, and began developing early instructions for Bashir to use.

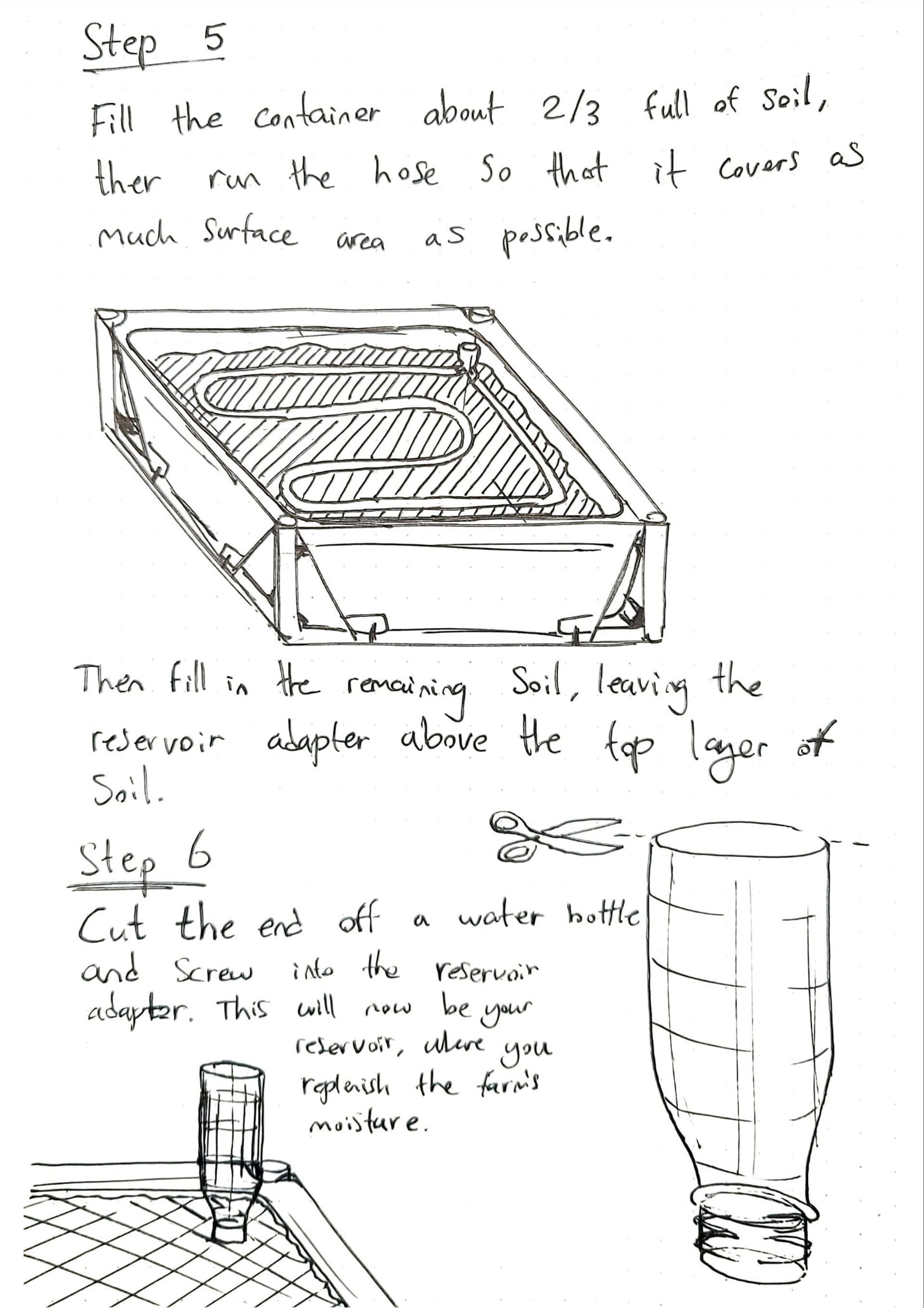

Starting to Develop Instructions

I began working on the instructions by creating sketches of each step, approximating how best to explain the process in a clear and intuitive way, with as little text as possible. The second phase was creating a digital version with CAD drawings instead of sketches.

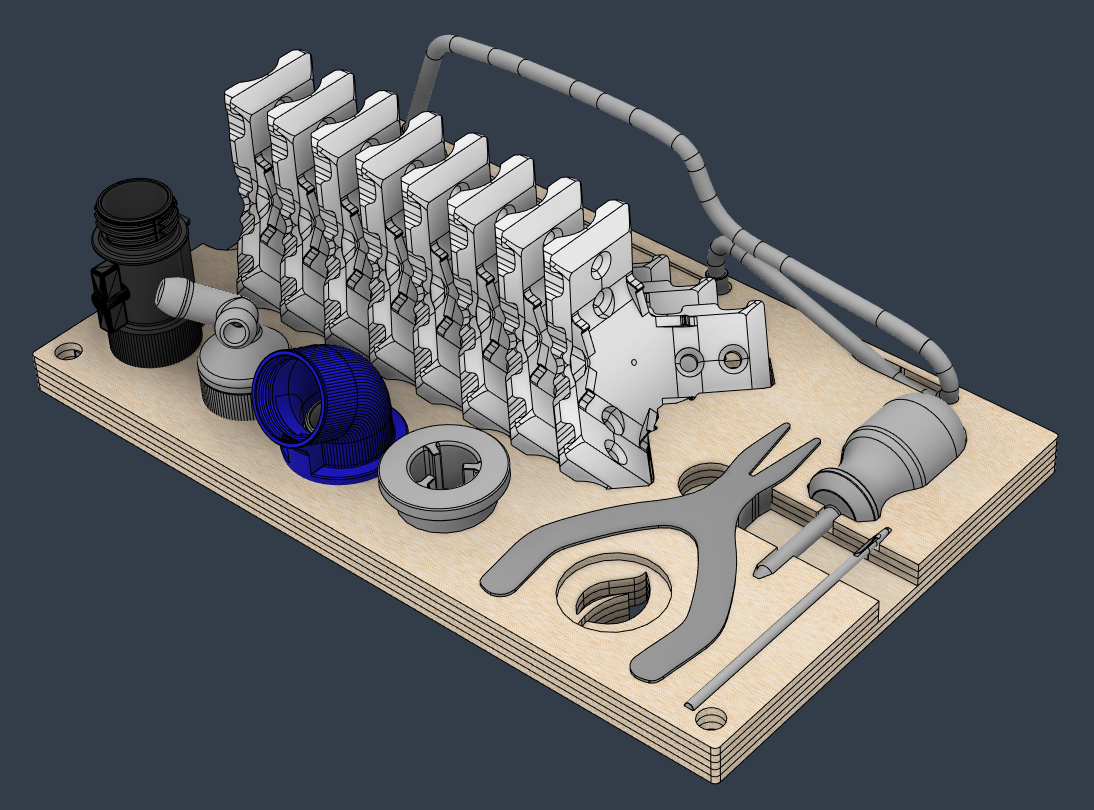

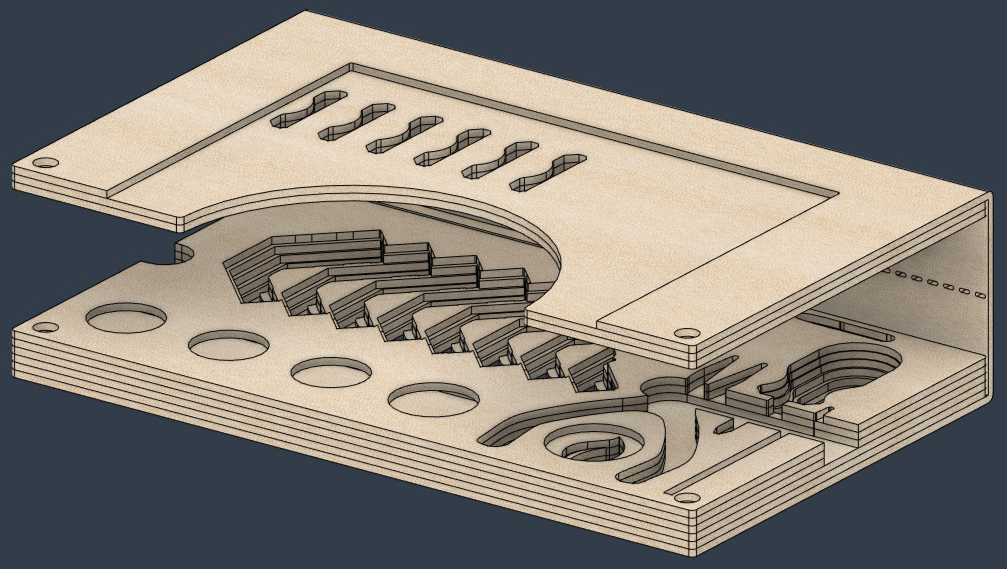

The Kit: CAD

Finally, I began to work on the kit: I made CAD models of all of the components, beginning with the bulkier tools and 3D-printed components, and created a layered cardboard cutout to hold each of these parts in place in a secure and protected way. The packaging would create a clamshell around the components which could be folded open to access them, and on the outside of this would be two half-boxes which would become germination beds for the seeds when unpacked. The clamshell would also feature a spot to place the a5 printed instructions, alongside a QR-code to a set of digital Instructions.

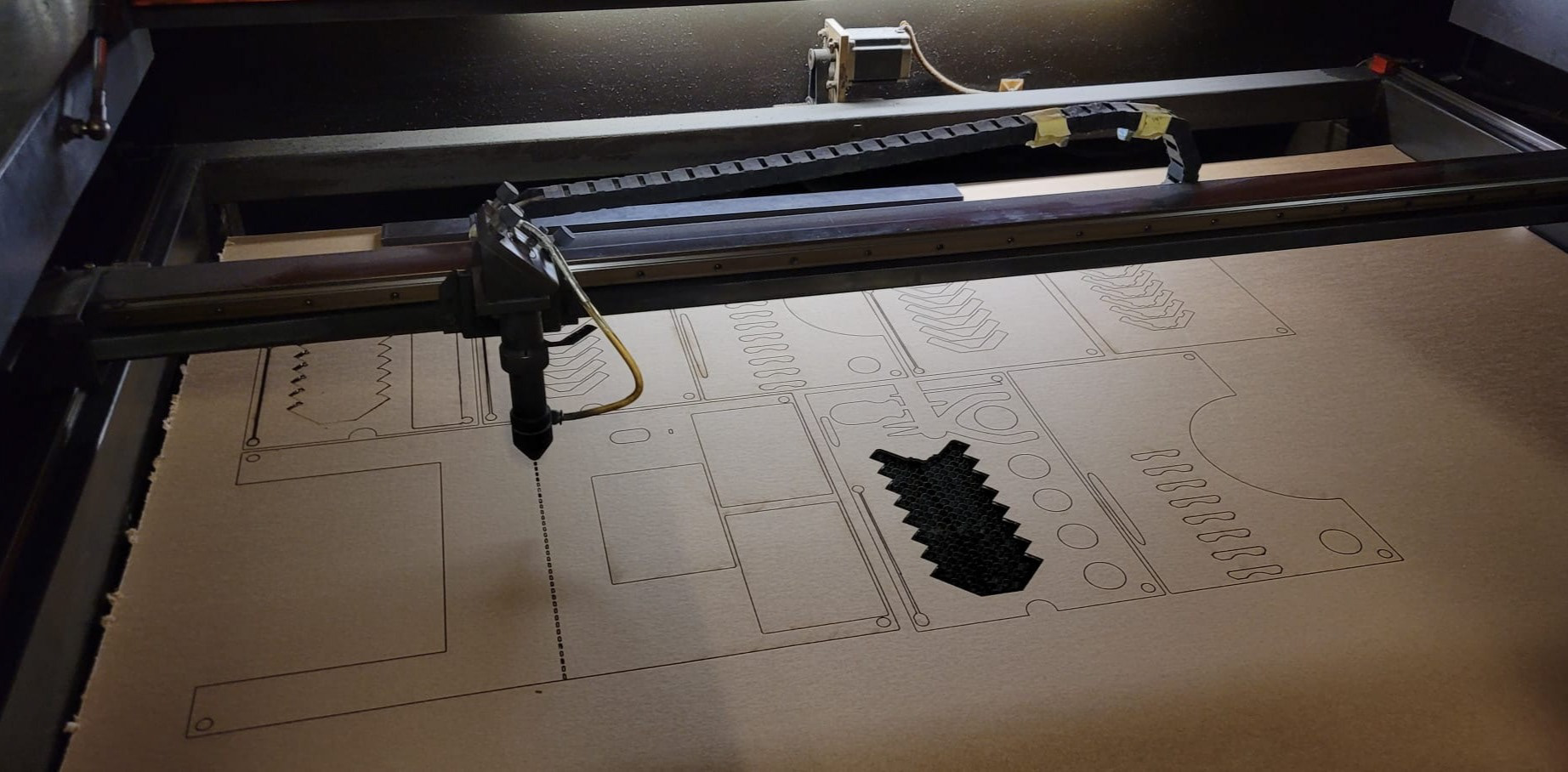

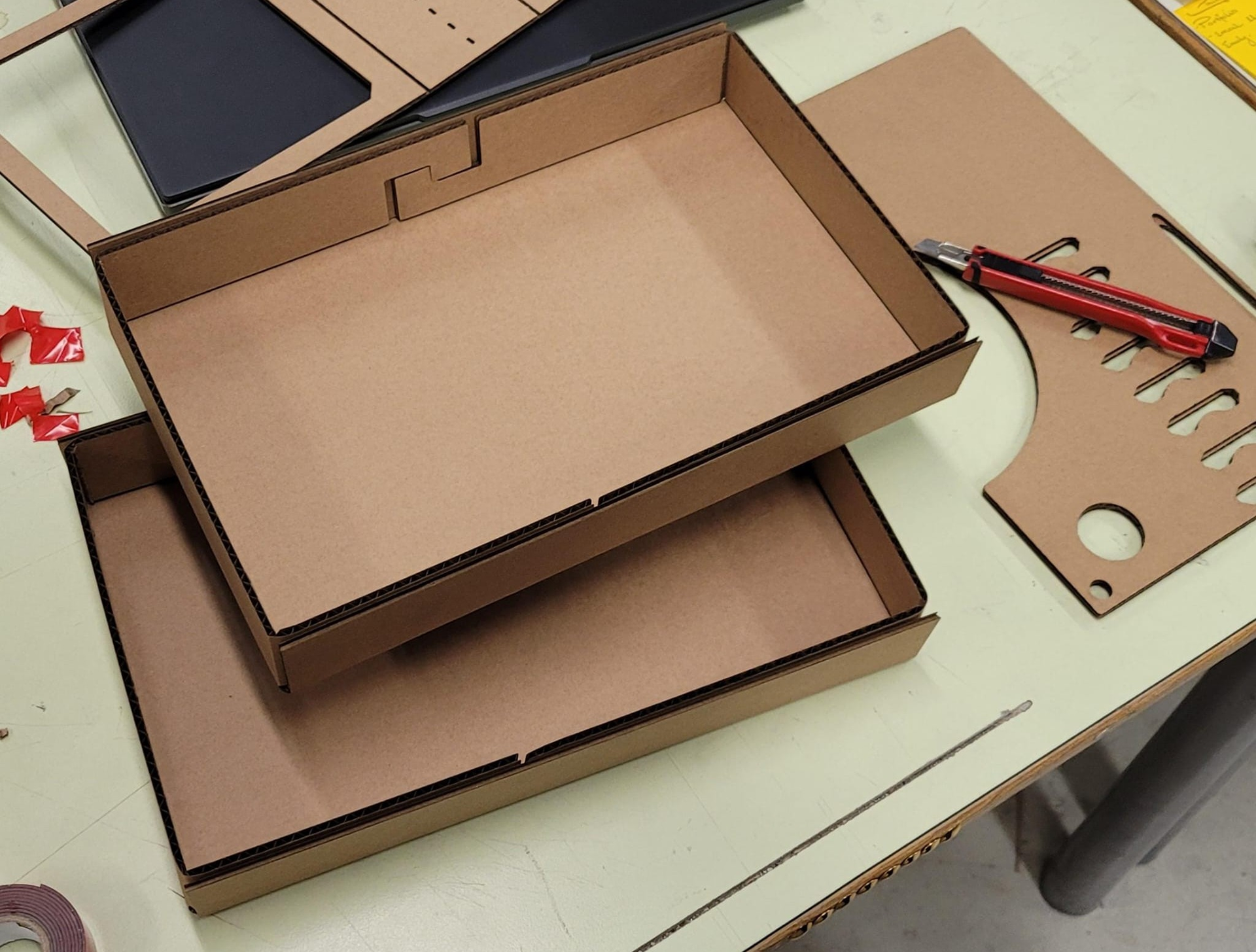

The Kit: Creation

Next, I turned these CAD files into .DXF files and imported them into Lightburn, a software for laser cutters. I then cut the profiles from 3mm corrugated cardboard, then layered them and fastened them together. I had tested the fit the tools into 3D-printed mockups previously so they fit perfectly. I also lasercut a perfect fit two-part outer box which would also act as germination trays for seeds to grow before being transplanted into the system.

Below the full box is shown as well as how it looks with the components removed.

Kit Final Images

Final System Prototype

Using the lessons I had learned from the previous prototypes and the components and tools in the kit, I built the final system prototype. The process was significantly simpler than the original iteration and it was neater and more flexible of a process than before as well

Finalising Instructions

I further developed the instructions, learning from my different prototyping attempts I had made, how to simplify the process of construction. I used light gamification techniques such as colour-coding of stages and progress markers to make the process more engaging. I also added blue bubbles which told users alternative methods of completing steps, especially in the case of different materials being used: I wanted the system to be possible to assemble with a wide variety of materials so I made the process very flexible.

User Testing

Bashir Al Awar, who I had previously spoken to about the project, and who works as a Farming Systems Engineer for ICARDA, had been kind enough to offer to assemble an early prototype of the kit himself, and test it at ICARDA offices in Beirut, Lebanon. This test would allow the system to be tested in a similar climate to that in the Syrian camps that this project targeted, as well as to test the assembly process with someone who had not yet been involved in this aspect of the project. Even after the end of this project the growth in this test system will be monitored, and future changes can be based on discoveries made during this testing.

Unfortunately it was not possible to get kits into Syria to test due to extremely strict border control. International shipping services such as DHL, DPD, etc. do not deliver to Syria, so testing in the real context was unfortunately possible within the timeline of this project.

Growth Testing Results

For my final presentations I brought my Scaled-Down testing boxes in, to show the progress that plants had made growing in this system over the course of the 6 weeks since they had been planted in. Many of the plants were already beginning to bloom, and would begin to yield food soon.

Through a combination of testing and expert research with Daniel Amoak and Bashir Al Awar, a suite of seeds had been chosen to include in the kit: spinach, courgette, French beans and tomatoes. These were chosen due to the speed of their growth, the rounded array of nutritional value that they provide, and their current popular position in Syrian cuisine, meaning that the learning curve for cooking and taking care of these plants would be minimised.

Visualisation

Through my continued working relationship with Khalil Al Taha, the CARE International Civil Planner in charge of Zoghara Camp, I received various images of the camp throughout my research, both on request to clarify infrastructure and material availability and to gain insights into the quality of life and needs of Inhabitants. The below image was one that Khalil sent, showing a project that a family in Zoghara had started: to grow plants in small plastic containers and jars. I found that this perfectly represented the determination and ingenuity of the people of Zoghara, and reflected the need for this project. I inserted an image of the Kindred Crop system into the image, and this will stand as a representation of this project.

Final Gallery